David Deutsch’s The Beginning of Infinity brims with ideas that turn conventional wisdom on its head. One especially eye-opening chapter in this book, titled “Unsustainable,” challenges the familiar notion that human progress inevitably stumbles over finite resources. Deutsch suggests that what truly brings about societal collapse isn’t the depletion of a particular resource, but rather a failure to keep creating new knowledge. It’s a perspective that, paradoxically, leads to optimism—even about environmental issues such as climate change—because creativity and innovation can render the “limits of nature” far less limiting than we might think.

One of the most memorable illustrations Deutsch draws upon is the well-known story of Easter Island. For centuries, the inhabitants of this remote island in the Pacific Ocean built giant stone statues, famously scattered across the landscape like silent sentinels. According to the standard narrative, the Islanders cut down so many trees for transporting and erecting their monuments that they ended up destroying the very means of their survival. Their deforestation fiasco, the argument goes, caused soil erosion, decimated fishing by eliminating wooden canoes, and ultimately sent Easter Island’s culture into a tragic collapse. At face value, this is a cautionary tale about “unsustainable” resource management—a tiny, isolated “world” undone by folly.

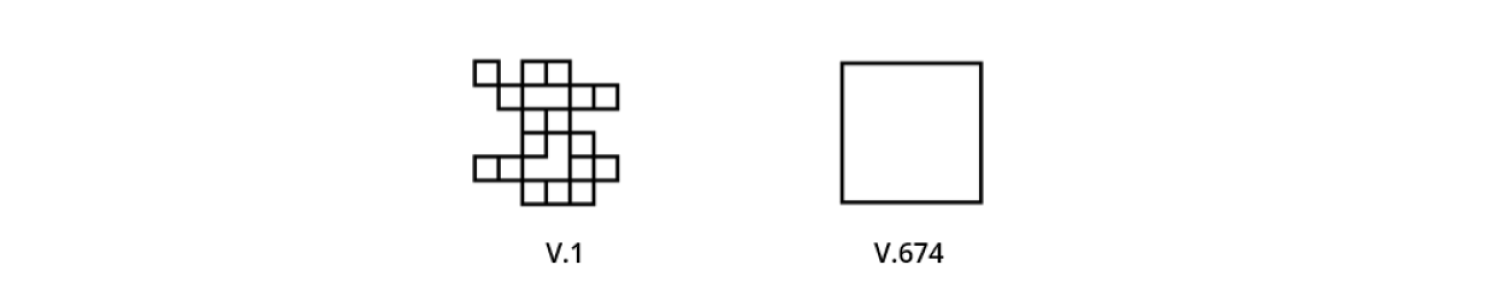

Yet Deutsch follows the lead of Jacob Bronowski, who filmed on Easter Island for his series The Ascent of Man, and sees a deeper lesson. Bronowski’s question was not merely how Easter Islanders got there, but why they never learned enough to leave, to trade, to expand. They could build enormous statues, but they couldn’t innovate when new challenges arose. Bronowski observed that these monolithic faces all looked alike, evoking a society stuck in cultural repetition. Meanwhile, another documentary giant, David Attenborough, draws a ‘Spaceship Earth‘ analogy: Easter Island as a kind of miniature mirror for the whole planet. In his series The State of the Planet, he worried that we are on a similar path, squandering our resources and tipping ourselves toward irrevocable environmental ruin—rather like the Islanders who toppled their statues.

Deutsch suggests that Attenborough’s analogy misses the most important factor behind the Islanders’ downfall: they belonged to a static society, lacking the sort of problem-solving culture characteristic of an Enlightenment-driven world. The real disaster wasn’t so much their forest mismanagement, but their inability to rethink what they valued (the statues) and how they lived. Even if overcutting trees was a miscalculation, every society makes miscalculations. The key to survival is correcting mistakes, finding new solutions, and refusing to be locked into endless repetition. This, Deutsch argues, is what differentiates a dynamic, knowledge-creating society from a static, tradition-bound one that tends to buckle under unforeseen stress.

In effect, Deutsch is saying that whenever doomsday forecasts arise—be they from Malthus in centuries past or from modern voices predicting imminent catastrophe—they hinge on the assumption that we will stop creating new ideas. Easter Island is the classic illustration of what happens to a society that loses that ability (or never had it in the first place). For centuries, Western thinkers have conjured up “limits to growth” by fixating on a single, finite resource and expecting calamity as soon as that resource runs out. In the 1970s, for example, some environmentalists fretted over the supply of rare-earth metals like europium—crucial for color televisions—and warned of an inevitable two-tiered world, where a fortunate few hoarded the last color sets while the rest languished. But that grim scenario never unfolded, largely because new display technologies—flat screens, LCDs, LEDs—got around the original limitation. Over and over, history shows that new knowledge can turn a so-called insurmountable shortage into little more than a footnote.

Deutsch doesn’t deny that real environmental crises arise. Rather, he insists that the crucial factor is whether we try to freeze our society in place out of fear, or instead double down on open-ended problem-solving. Environmental issues like climate change illustrate this tension. Some proposals urge severe lifestyle restrictions to stave off future damage. Others ask whether we should throw our energies into innovating our way out—be that through cleaner energy sources, carbon capture, geoengineering, or solutions we can’t yet imagine. Deutsch’s central point is that a “sustainable” society in the sense of never changing is itself dangerously unsustainable. Without ongoing innovation, sooner or later a new problem—an unexpected climate shift, a mutation in pathogens, a drought, a virus—will appear, and a static world will be no more prepared than the statue-builders of Easter Island.

Consider how different things might have been if Easter Islanders had discovered new ways to reforest, or to sail off the island for supplies, or to question the tradition that placed statues above the trees they desperately needed. Their plight shows that human creativity, once stifled, leaves little defense against nature’s curveballs. But our modern, pluralistic, and knowledge-driven society is in a far better position—if, that is, we remain faithful to our capacity for generating explanations and devising solutions. Suppose climate change intensifies. Deutsch reminds us that if these trends had happened a century earlier, humanity would have been far less equipped to handle them—science, technology, and wealth were not nearly what they are today. It is precisely the growth we have already achieved that places us in a stronger position.

So, Deutsch’s chapter “Unsustainable” in The Beginning of Infinity isn’t a glib denial of environmental threat; it’s a powerful reframing of our fears. Resource depletion, climate disruption, and population booms cannot be waved away, but neither should they be considered final. Solutions will themselves cause new problems—any major advance brings unforeseen consequences—but that is how progress goes forward. There is no perfect equilibrium, just an unending sequence of problem-solution-problem, in which knowledge grows and human beings continue to flourish.

In urging a view of society as capable of infinite progress, Deutsch is no stranger to skepticism. After all, the entire thrust of environmentalism often centers on “limiting” human activity. But he insists that the urge to limit, contain, or sustain in a static sense is actually the path to collapse. The moment we embrace self-imposed stagnation, we regress into an Easter Island mindset, building ever taller statues while our future silently rots from underneath us. By contrast, if we accept that we will never be fully “sustainable”—if we recognize that each solution is just a stopgap pending our next discovery—then we open the door to an ever-expanding future.

To Deutsch, that is the greatest hope. From the vantage point of creative thinking, we need not fear that tomorrow’s challenges will be our undoing. We have a track record, however imperfect, of surmounting problems that yesterday looked insoluble. Embracing that tradition of criticism, wealth creation, science, and daring might be our best bet, not just for surviving climate change, but for embracing an unbounded future. It’s certainly how we can avoid building statues in the desert while our forests dwindle—and how we can leave behind the toxic assumption that we’re all trapped on a tiny island with no way out.